interview: Caleb Hammond

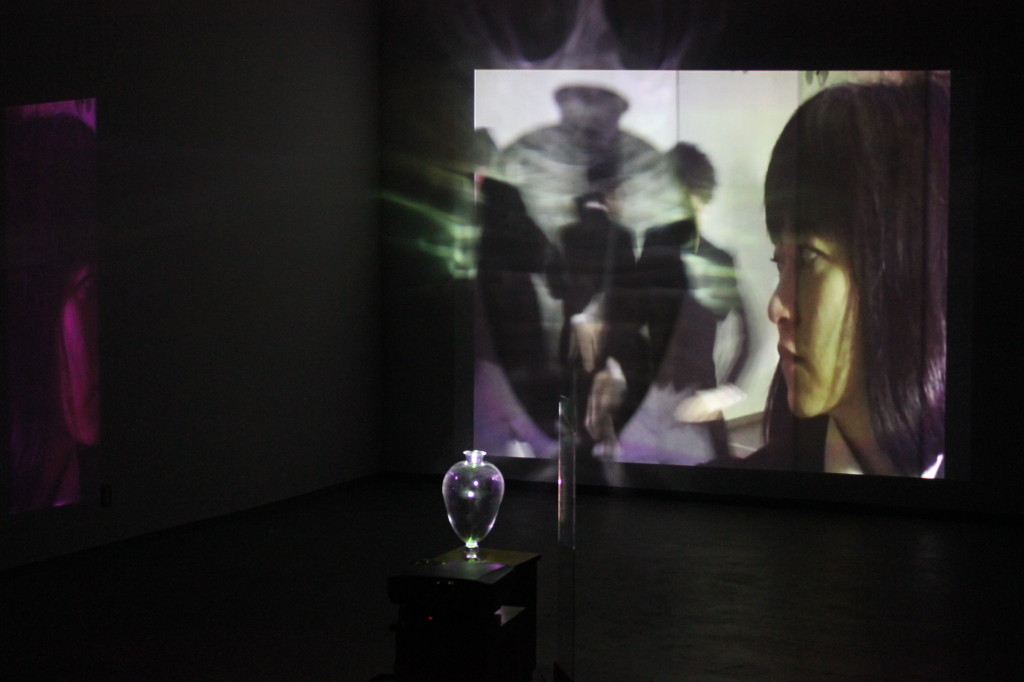

Elegy 1: After Rilke (2014, created in collaboration with Sean Salstrom)

Elegy 1: After Rilke (2014, created in collaboration with Sean Salstrom)

Caleb Hammond is a theater director and visual artist. In addition to his extensive work as an actor and director, Hammond’s original production The Irresistible, which he adapted from texts by Ibsen and Euripides, premiered this April at the Immersive Gallery in Brooklyn. This interview took place over the course of two fall afternoons in the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn, where Hammond works and lives. Hammond told us about his affinity for Rilke, his thoughts on Robert Bresson's directing philosophy, and why he's drawn to the ephemerality of theater.

I first met you during your production of The Irresistible at the Immersive Gallery. Can you tell me more about that?

CH: The play I did at the Immersive Gallery was a crossing, or a mash-up, of Hedda Gabler and The Bacchae. I took these two cornerstones of the dramatic canon and I put them side by side in this space, this warehouse. We made it a space that you could walk through. Both plays were happening simultaneously and crossing over into one another. It definitely had an immersive element, so the Immersive Gallery was an appropriate venue.

Why do you think we’re seeing more immersive theater these days?

CH: For a lot of reasons. It’s something that you can’t get—not right now, anyway—out of your cell phone or a screen. These days we’re so immersed (to overuse that word) in screens that are virtual or flat, which feel immersive to us, but they aren’t really. They aren’t real or tangible. One thing theater can do that film can’t do yet, or the Web, is to surround the audience with the experience. Theater brings people back into real space.

Do you think about real space and virtual space when you’re staging a play?

CH: When I’m staging a play that’s immersive, I’m thinking about how I can open up a space so that no matter where the people go, it will be interesting. In The Irresistible, we had a video screen set up, so people could be watching what was happening in the other room simultaneously. For one of the performances, I opened up a pathway by the side of the stage, so people could do a complete orbit, a complete circle around that stage. I really liked that. There were a lot of plants that sort of obstructed the view, so it felt like being on a movie set. Or a television set. I liked that. I think using space in that way isn’t a reaction to the Internet—it’s not in opposition to the Internet—but it is drawing from that same way of looking at the world. There’s a back and forth. Even in a traditional theater with a straightforward proscenium, it’s impossible to make the experience the same for everyone. I try to make sure every seat in the theater has a good sightline. But in a three-dimensional space, there are a lot more options. It makes the viewing more active.

Beyond New York, you’ve also produced work in Europe and Japan. Did you feel a particular affinity for those other places?

CH: Yes, definitely. Number one, it always feels exciting to be an artist from one country presenting in another. Immediately you are exotic. People are interested in you because you’ve made a long journey. You’re unusual because you’re not from there. There’s an aspect of, if you’re presenting something there, of people listening very closely, or in a different way, whereas here, I’m just one of a million American artists. In Europe, they’re used to having a lot of Americans, but in Japan, there are Americans there, but you definitely get the sense that you’re exotic.

You’re the eccentric foreigner.

CH: Maybe. [laughing] But beyond that—that’s one side of it—and I’ll speak just about Japan right now: There’s a whole different way of looking at aesthetics there, and a whole different way of combining aesthetics with life, that I find very appealing. There’s a sensibility, an aesthetic sensibility, that’s all around you in Japan. Even in the urban areas, and the very commercial areas, there’s a sense that real care has been taken for the way that life is experienced, which also feels part of their art. As opposed to here, it doesn’t always feel that way.

Have you ever tried to incorporate that feeling into your work?

CH: Yes, but not exactly. Not to make a copy, not to make a replica of a foreign place. But more to reproduce the feeling that a foreign experience had on me. Travel always changes me. It helps shake up my point of view. If I travel somewhere, where I get immersed in the culture or I get immersed in a different way of looking at things, I come back and it’s not like I’m seeing America with “Japanese” eyes, but I am looking at things with an expanded view, because I’ve been opened up to different ways of looking.

________________________________________________________________________________

When you collaborate with other people, if they’re good people and they’re listening—when the collaboration is working really well—it feels like you can reach something that neither of you would have reached on your own.

________________________________________________________________________________

What were you working on in Japan?

CH: In Japan, I was working on a video installation piece in collaboration with a master glass blower, Sean Salstrom, at the school he teaches at there, the Toyama City Institute of Glass Art. It’s one of the top glass schools in the world—definitely in Japan. So it’s this amazing cauldron of creativity, where people are working on glass in all the different ways that glass can be used. And Sean, the artist I was working with, is an incredibly prolific and creative glass artist. When I went there, we didn’t have a specific goal in mind, but we had this idea that we wanted to use video projection—light with glass—and see how we could treat that, sculpturally. We talked about different topics we could use as an anchor, as content, and we landed on the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, which we both loved. Specifically, his Duino Elegies.

So much of your work uses other pieces of art in unexpected ways—it’s almost a reenactment, or a translation of other artwork. What is going on there?

CH: For the first 10 years I was producing my own work, I was more clearly writing. It wasn’t translation. It was original writing. Now, I guess, in the second 10 years of my professional work, I’ve been doing a lot of using other people’s pieces as a sort of script. I think translation is a good word for it. The work that I did early on was very… I don’t know if I should call it poetry, but it wasn’t narrative, it wasn’t linear. It had a more poetic feeling to it in the text, and in the way that it was staged. It’s interesting how you can put something on stage that’s not necessarily grounded in a strong dramatic arc. It’s more poetic.

In the piece you did with Sean Salstrom, you actually chose the glass and video projection as your medium before you chose Rilke’s elegies as content. What was that process like?

CH: Normally I would start with the content. Rilke is somebody whose poetry I’ve wanted to work with for a really long time. I’ve thought before about how to translate his poems for stage. So in a sense, that idea did come first, and then it was just a question of waiting for the right project to arise. When Sean and I started talking, it was because we wanted to work together. It’s important to like the people you’re collaborating with. In Sean’s case, I had seen a lot of his work, and he had seen mine, so there was a sense of familiarity with the types of ideas we like to pursue. He was teaching at RISD at the time, but then he got the job in Japan, and he was able to bring me in as a visiting artist. So, in a sense, it was all about waiting for the right opportunity. There’s something in the process of making artwork that is just as important as the content.

A lot of the work you do is collaborative. I’m a writer, so usually I’m working alone. But you’ve done both, so I’m interested in that difference.

CH: That’s something I think about a lot. I started off as a studio artist, and writing on my own. I was always in my studio alone, or writing on my own. I started bringing other people into my work primarily because I was spending so much time alone. It was feeling like an echo chamber, a little claustrophobic, and I started to get sick of myself. I like the flexibility of collaboration. When you collaborate with other people, if they’re good people and they’re listening—when the collaboration is working really well—it feels like you can reach something that neither of you would have reached on your own. Often I am framed as a director, and there is a certain hierarchy in that. Not always, but often. Often I am the one instigating it. But it’s great when I have an idea, or a concept, or a direction that I’m going in, and collaborators take that and think about it, and they come back with something that’s very different, or they take it to a different place that I would never have thought of. That’s really exciting. Then sometimes I get tired of working with a lot of people, too. It’s nice to be able to switch between the two modes.

What’s the difference between writing for actors and writing for readers?

CH: When you’re writing for people to read you, it’s writing for an audience of one. When you’re writing for performers, it’s writing for a much bigger audience. You’re writing for other artists to interpret, or translate, so you’re talking about translation again. I think that’s key. The actor’s performance is automatically an act of translation, even if it’s not a radical translation. The director’s aim is to get as close to the text as he can, and with actors it’s the same thing. They’re taking the text, along with whatever the director is telling them, and the scenery, and the set design, and combining all of that with their own interpretation of that world, into a performance. So if you’re writing for actors, as opposed to writing for the page, maybe it needs to be a little bit more open in a certain way. It’s slippery to talk about because, in some ways, writing for one person allows you to be open in another type of way. You can go into a different complexity of language if there’s one person who’s tracking very closely with you.

Scene from The Irresistible. Image courtesy Maria Baranova.

Scene from The Irresistible. Image courtesy Maria Baranova.

Who are some of your favorite actors that you’ve worked with?

CH: Right now I’m working with Anna Kohler on a play that she’s been writing. I’m helping her develop it. It’s phenomenal working with her because she’s worked with a lot of great film and theater artists. She’s a little bit older than me; she’s up there with some of the people I really loved as a young theater student. So that’s exciting. There have been a number of those artists and actors, like John Hagen, who played Teiresias in The Irresistible. It’s exciting to have reached that place where I can work with people whose work I fell in love with from the audience. That’s very exciting on a personal level.

What is Anna Kohler’s play about?

CH: It’s still in progress, but it starts by focusing on one moment of Anna’s life. It’s her memory of that moment, from a time when she was about 19 or so. She was studying acting in Paris, and working as an artist’s model in Paris. So we’re focusing on that moment, it’s kind of that—that ah-ha! moment, which many of us have, as humans and also as artists—where the world opens up in a major way. This thing is not quite like having arrived somewhere, but it’s like suddenly the world is open to possibilities in a way you didn’t know before. She talks a lot about having come from Germany, where she felt she didn’t really belong, and then getting to Paris and being very excited. The big step for her is when she goes from Paris to the south of France because it’s unlike anything she’s ever seen. It’s a sensory overload. We’re trying to contain all of it somehow on the stage, this sensory overload. It’s also about her experience of being an artist’s model, where she learned a lot about stillness, and about the power of presence, which has really informed her acting. We’re drawing on the films of Robert Bresson, a French filmmaker whose work she was seeing a lot of at that time. Bresson wanted his actors not to be actors but to be models, in the way of a painter’s model. We’re interested in that relationship of the director, or the filmmaker, as an artist who’s trying to draw out the actual person, or the actual spirit of the actor, as opposed to a performance.

Do you ever have those kinds of tensions with your own actors?

CH: There are different ways to have tension. There’s a difference between maybe the actor doesn’t understand me, or they’re scared—there’s a difference between that and if the actor continually thinks what I’m proposing is wrong. Then we shouldn’t be working together. If it’s a situation where I’m not clear enough—which happens because I’m often after ideas that are esoteric, or ways of performing that aren’t so literal, and I’m looking for the kind of stuff that’s I know it when I see it on the stage—It’s hard to get there because it’s hard to talk about. So it’s inevitable that working with actors can sometimes lead to frustration. But when the tension is coming from a shared place of passion, or a place of wanting to get the art produced, it can be productive tension, although it’s hard.

Do you agree with Bresson’s philosophy of directing?

CH: Bresson has a great book that we’ve drawn on a lot called Notes on Cinematography. It’s a really fascinating book. It’s just a lot of short thoughts on acting. “No acting, just being”—it’s very French—and “Don’t think what you’re doing, don’t think what you’re saying.” Also, “Don't think about what you say, don't think about what you do.” It’s about getting the action closer and closer to just doing something, instead of thinking about it. If an actor keeps thinking too much about what he’s doing, then Bresson finds that false.

When you’re picking a new project like this to work on, how do you choose?

CH: This one’s interesting because Anna asked me to work with her. We had already worked together on another play in New York, which I was the assistant director on. We met then, and she was telling me about this project. We had a great conversation about it. She’d been working on the material for a while, and she wanted to bring in somebody to help bring it to performance. That was unusual, for me—that doesn’t happen often. Usually it’s me deciding the next piece. I have a couple pieces that I’m thinking on, for example, right now, in my brain. Often now it feels like the next piece is being born in the piece that I’m finishing. There is always something, some little aspect of what’s happening in one piece that I want to look at closer in the next piece.

What’s the longest you’ve ever worked on one play?

CH: There were a couple of different pieces I worked on over a period of a few years, but I would be doing other things in-between. It would be in the background, and I’d come back to it. The Irresistible we worked on for probably two years, but most of the time I wasn’t actively working on it. There was a solo piece I did when I was about 25 that I toured in different variations for about four years. That was probably the longest run I’ve done. It took me about a year to make it—to write it and make it—and then I toured it. Intermittently, other things were happening.

What was the shortest run of a play you ever had?

CH: One day. I’ve had a couple of things that were one day.

Scene from The Irresistible. Image courtesy Maria Baranova.

Scene from The Irresistible. Image courtesy Maria Baranova.

That’s amazing to me because there is so much work that goes into the experience that will only stay in people’s memories. Why do you do it?

CH: That’s a great question. Theater is ephemeral. I think there’s a power to that ephemerality, the sense that this is not going to be repeated. Even if it’s a long run, eventually it’s going to end and people are going to go their separate ways. In the case of an ensemble piece, there’s a real community that’s formed around it. You’re going to see the same people at rehearsal, and there is the performance every night, and then it ends. But there’s something kind of beautiful in that, in the ephemerality. That the experience is special because it’s based in time; it’s fleeting. It can only be remembered.

Have you ever thought about the way “playwright” is spelled? Would you ever say, for example, that you “wrought” a play?

CH: I think that’s intentional, because you have wheelwrights and all that. I haven’t done a lot of historical investigation into the origins of the word, but when people were first becoming playwrights, I think they would work on words like that. You would go to a wheelwright to get your wheel made, and you would go to a playwright to get your play made. I think that’s a lot like how television gets written today, too. There’s this feeling of it being a craft—

That it’s manufactured?

CH: Manufactured, maybe. Maybe that feels negative to people like us, who think of it as art rather than a craft. Maybe there’s a humility in craftsmanship. Or an honor in it.

Interview by Rachel Veroff.