in review: Contesting Modernity: Informalism in Venezuela, 1955-1975

Dámaso Ogaz, FUBW (1968)

The question of representation and realism in art was once of great importance. Could the fractured perspectives of Cubism or the emotional mindscapes of Expressionism carry universal significance? Could abstract art convey any political weight or importance? So raged the debates of the early to mid-20th century.

Looking back, it seems inevitable that modern art would turn toward increasingly non-figurative work. As consumer culture fetishizes individuality, perspectives on art have largely followed. Art, we decided, was meant to present our own unique experience in the world—and how could we convey our individuality while attempting to stay within the norms of photo-realistic representation? The development and widespread proliferation of photography further dulled the value of realist art. So, too, did efforts by the CIA, which promoted abstract artists in a subterfuge campaign during the Cold War.

It is difficult today to understand this tension. America was locked in a world-historical battle with the USSR and communism was a still-plausible alternative mode of socioeconomic organization. It was another time, before the End of History, when we had not yet associated socialism with the bogeyman of present-day Venezuela.

This history cannot help but factor into the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s Contesting Modernity: Informalism in Venezuela exhibition. This comprehensive collection of work, created between 1955 and 1975, complicates our narrative, reminding us why abstract art proved compelling while reinforcing how it can function as a potent political tool for artists on the Left. At the same time that Abstract Expressionist artists like Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko were being promoted by the US as emblems of capitalism’s cultural power, artists like Carlos Contramaestre and Elsa Gramcko were exploring new avenues of artistic expression, thumbing their noses at their country’s arts institutions and using unconventional materials to draw attention to society’s ills.

Francisco Hung, Pintura no. 5 (1964)

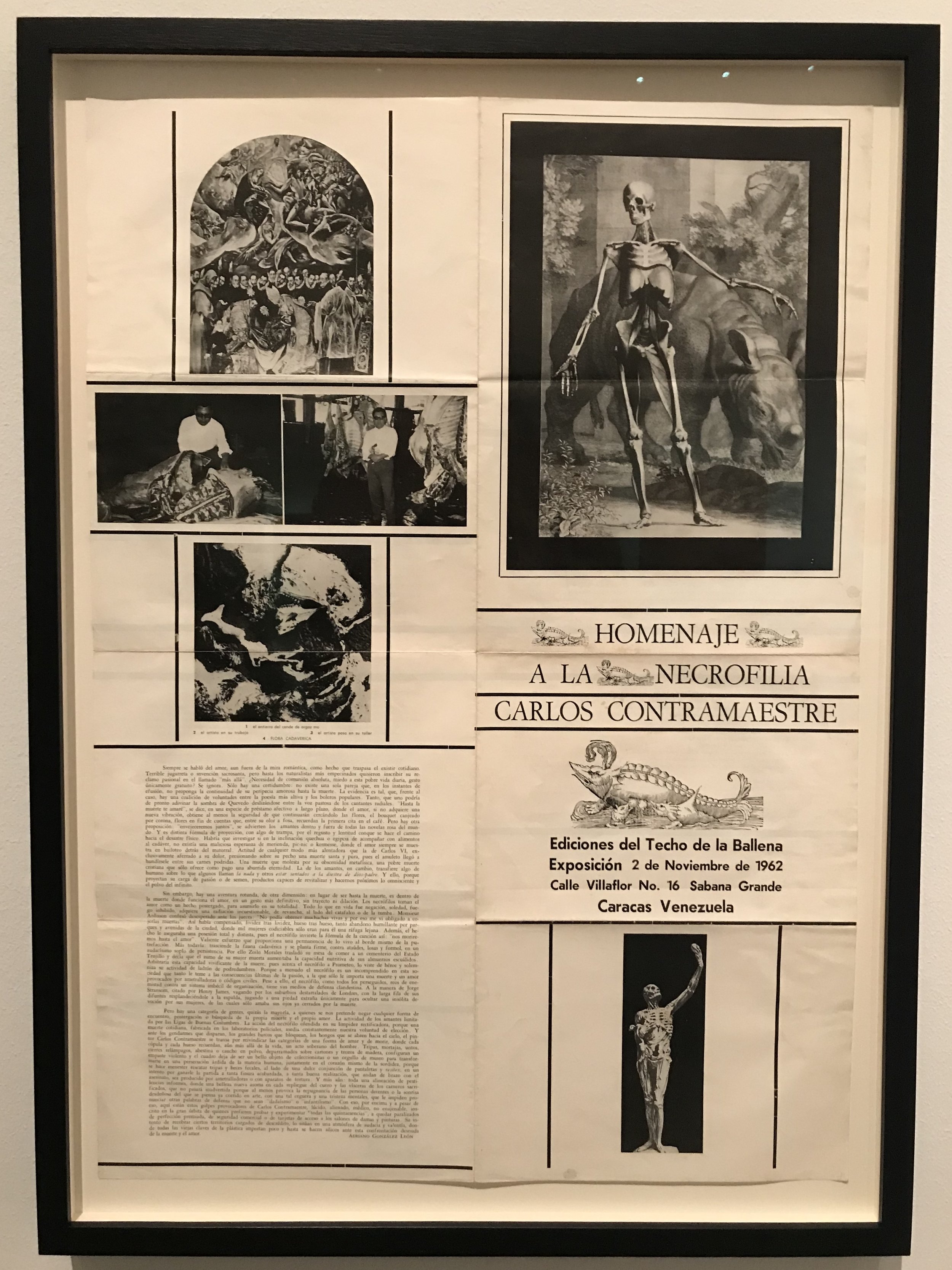

Fine art, at its root, is a paradoxically reactionary institution, even when its practitioners push the boundaries of social mores, ostensibly in pursuit of progressive ideals. This tension bears out in the work of Francisco Hung, whose Pintura no. 5 features a dance of ghostly phalluses across an explosive blood-red backdrop, and Carlos Contramaestre’s Homenaje a la necrofilia (Homage to Necrophilia) exhibition, which featured animal bones, blood and waste products on canvases. The latter exhibition caused an uproar upon display in 1962 and was quickly shut down by the Venezuelan government. Such artwork today would be greeted with skepticism for its easy shock-value appeal, but there were political dimensions to the work which bear consideration. As Contramaestre put it, “it was necessary to respond to the violence of the government… with armed violence, which was already occurring in the country, [but also] through the uses of literature and painting.”

Contesting Modernity is framed as a reaction to the “rapid social transformation and income inequality” that came with Venezuela’s transition from dictatorship to democracy in December 1958. The exhibition does not go into details of this “rapid social transformation,” blandly attributing it to the pains of transitioning from dictatorship to democracy and inserting “income inequality” as a referent that will resonate in contemporary America. This is not surprising, given the museum’s tendency to absorb countercultural elements while excising any threats to the system that allows it to function. But viewers should know that the president elected in 1958, Rómulo Betancourt, first came to power 13 years prior to his election through a military coup. The “Father of Venezuelan Democracy,” Betancourt instituted universal suffrage and brought significantly increased oil revenues to the country, but he also oversaw the widespread arrest of Communist Party members and the suspension of civil liberties. Guerrilla warfare with revolutionary Leftist groups persisted throughout the ’60s and served as the social backdrop to many of the exhibition’s works.

It is not my intention to critique the politics of these artists, and I do not have the necessary historical background to do so. I hope only to contextualize the work’s creation, while exploring the original question: Can abstract art offer a viable political statement? Judging by the works present, the results are mixed. Fifty-plus-years of sensationalist art have dulled the radical nature of many of these works, and a lack of historical clarity reduces the pieces to mere commentary on the need for environmental sustainability and commonplace critiques of consumerism and oil dependency. And the museum itself presents obstacles: The anti-bourgeois political work of El Techo de la Ballena is situated alongside the geometric and Kinetic works of Alejandro Otero and Jesús Rafael Soto, demonstrating not so much incoherence in the exhibition but art’s limited ability for structural transcendence. In an accompanying text to Contramaestre’s Homenaje a la necrofilia exhibit, Adriano González León proclaimed Kinetic art to be “so much cowardly refinement, such wonderful achievements that walk arm in arm with murder, whether it be produced by machine guns or by instruments of torture”— yet, Contramaestre’s and Soto’s works occupy adjacent rooms in the exhibit.

Show brochure for Carlos Contramaestre’s Homenaje a la Necrofilia exhibition (1962)

Nonetheless, a handful of works demonstrate the power of abstract art as potent political statement. Dámaso Ogaz’s FUBW (1968) channels the visceral impact of Contramaestre’s work into a more focused critique of authoritarianism. The piece, named for the Fascist Union of British Workers, shows the dehumanization that fascist ideology entails, with an ambiguous blend of human and animal limbs lodged in a series of pipes. Inserts of human faces are juxtaposed against the pipes, perhaps as referents to the humanity that has been lost. The piece succeeds for its potent blend of symbolism and intrigue while maintaining sufficient grounds for meaningful interpretation.

The relatively unknown Elsa Gramcko is the highlight of the show. The artist is rarely shown in the US, which is surprising, given her striking original vision and the substance of her work. Although her pieces are almost entirely abstract, they combine geometric experimentation with strong organic components that fuse the biologic with the industrial in unsettling ways. Pieces No. 20 and No. 21 (1958) look like mechanized bone structures, hinting at a transhumanist future that grows more prescient by the day. Her later work juxtaposes organic materials with car batteries, headlights, and other industrial parts, presenting a politically charged counterpoint to the scrap-metal sculptures of John Chamberlain. Pieces like El sol ha descendido (The Sun Has Descended, 1967) transform car parts into utterly alien remnants; juxtaposed against a metal grate, a car headlight gleams like a microphone that has been unearthed on a foreign planet. Is this, she seems to ask, what will become of us?

Gramcko’s works succeed because they fuse art’s symbolic gestural power with the weight of reality and ideological coherence. They appropriately contend with, as Lukács expresses it, the “objective essence of reality.” This is rare among artists—rarer still among artists glorified by America’s capitalist fine arts system, which often rewards the precise opposite of such approaches. Is it little wonder that Gramcko is unknown in our country?

Elsa Gramcko, No. 20 (1958); No. 21 (1958); El sol ha descendido (1967)

For those more concerned with form (this is a show about Informalism, after all), there is much to appreciate. José Maria Cruxent’s pieces—particularly Sans erotisme il n’y aurait pas d’amour (Without Eroticism There Would Be No Love)—are stunning mixed media compositions of grand scale, their oblique titles adding emotional weight to these metaphysical explorations. And Carlos Puche’s iron objects, presented against shadows both imprinted and real, are elegant explorations of time and space. These and a number of other artists on display demonstrate the innovative incorporation of non-traditional materials into their work, showcasing the importance of the Informalist movement to the country’s artistic development.

José Maria Cruxent, Sans erotisme il n’y aurait pas d’amour (1965)

Contesting Modernity is a show that is grounded in its time and place, but whose insights offer relevance to our present moment. As we consider Venezuela’s slide back toward dictatorship, its art from this time is preserved as a historically important marker of the tensions between ideas and expression, the personal and the political. What is the power of democracy under capitalism, and what is the role of art in such society? These are questions we must continue to consider today.

—Sean Redmond

Contesting Modernity was on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, from October 28, 2018–January 21, 2019.

Carlos Puche, Objetografía no. 20 (1965)